Since my post last month on a “what if” about farmers being able to participate in brand value creation with the consumer brands, I’ve received some interesting and inspiring responses. They come from people in executive positions at a leading global food brand, and at a commodities trader, as well as from a relatively well-known marketing innovation expert and blogger.

In this post I would love to share some of the insights of this exchange. Because it’s not appropriate to present the reactions with direct attribution to the respondents due to the informal nature of exchange, I have chosen to reform the responses into a fictive conversation. The conversation is between me, as an interviewee, and an “industry journalist” enquiring into next step innovations on sustainability, marketing and supply chain operations in food and agriculture. A little schizophrenic and unintendedly vain maybe, but bear with me…

Q: This idea you have connecting farmers to brand value and marketing is a nice idea, but isn’t this just a classic Michael Porter problem statement: some companies will prefer a strategy of backward integration into their supply chains, some won’t? If consumer brands use their resources for their producer partnerships, they will not be able to utilize them in their relations with customers.

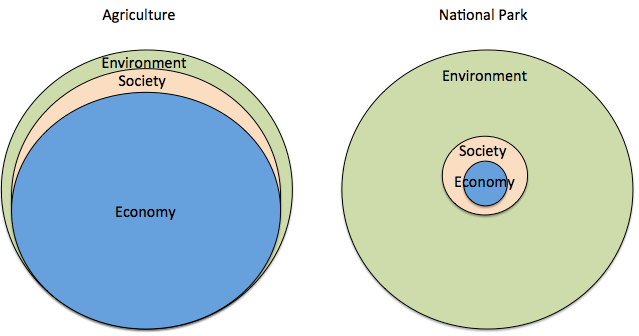

A: The dynamics in agriculture is turning very much to the disadvantage for firms that have been divesting out of production for the last decades. Natural resources are dissipating; farmers are not investing in their holdings, or as less as possible, due to low returns. Both economic returns and the environment suffer. People have been moving out of the farming practice all over the world. That is economic erosion, and it is a compounding risk of food insecurity. We need new propositions to keep farming attractive. People need to actually be moving into the business, rather than moving out, and food companies need to innovate in our food systems to secure their existence as a commercially viable company. That is what motivated my previous post, pointing to the need for new types of entrepreneurial propositions to farmers that are beneficial to food industry at the same time. It was not so much that I wanted to “push” a specific solution.

Q: Ok, for argument’s sake, let’s say you have a point: aren’t you focusing too much on added (brand) value systems? What about the commodities business, would your argument still hold?

A: Right now there is so much decline of environmental and social capital going on as well as a mounting risk of food insecurity all impacted by developments at the level of the primary farming activity. It is aggravating to such an extent that preventing that decline or taking action to invert that trend is actually the fastest growing value creating opportunity in agriculture at the moment. This type of value is not concerned with company-to-consumer value per se, it concerns the whole agri-food system, thus commodities and branded products alike. I think there is great innovation potential for the whole sector in linking back the value capturing capacity of down stream to the up stream area in the value chain where all the problems are stemming from.

Q: Sharing value across the chain, isn’t that another form of wealth distribution, and shouldn’t we have learned over the years not to use that type of socio-financial engineering?

A: What we have learnt about that, I think, is that you can’t centralize the redistribution function, like through government and taxation. And personally I would say that banks and derivatives alchemy actually belong on that same list (hahaha). What I propose with my idea, rather, is to unlock the potential of market based valuation of solutions to environmental and social problems. We’re already spending money through redistribution mechanisms in developing countries for instance; it’s called aid, and it’s really not working that well because it is spent regardless of any result.

Contrary to aid, market based valuation is contingent on performance, on achieving a superior allocation of resources. Rewarding that type of performance is the ultimate entrepreneurial proposition you can make, and it spurs innovation. Just look at what’s going on in Silicon Valley. The opportunity of creating and capturing value in the tech market generates unparalleled entrepreneurial pull that makes people from all over drop everything and move to Palo Alto. I know things are a bit crazy there, but if we could only unleash, or distribute, that type of spirit to agriculture in some way.

Q: Just stepping aside from theory for the moment: It just seems so impossible to make this work from an operational point of view. How will you reach these farmers, and what if the stock price goes down?

A: I agree that the idea would be a laborious undertaking. You would need to get thousands of farmers organized under a vehicle that could hold the derivatives and distribute returns. But then again, we have been investing in the setting up of large numbers of, oftentimes sizable, farmers’ organizations, in both developed and developing countries for years. We’re already building such infrastructure to facilitate product flow through the supply chain. New value systems could be used to strengthen the economic foundations of such collective organizations.

Secondly there is indeed and important issue of valuation an attribution of value changes. I know that brand valuation is not an exact science, but is valuation ever? But I think the need for valuation techniques could become so important in future that we should encourage more study, rather than put it on the back burner in solving the world’s food problems. Numerous companies have been developing metrics to track performance of their marketing departments using esoteric valuation methods. Also top-line ad-agencies use contingent contracting forms to determine their reward for advising their clients on advertising and creating brand value. Why not take it from there, and look at your producer partnerships?

Regarding the point of fluctuations in stock prices, I would say that if attribution can be correctly constructed, it then wouldn’t really matter if value drops. It would mean that performance has gone down accordingly. Remember, that the idea is intended to be an entrepreneurial proposition; no performance, no reward, and each partner carries the risks of the joint value creation endeavor accordingly.

Q: If the example you provide is not actually a real solution as you say yourself, or at best too complicated, what would you then propose to do? What can companies practically work with to start on the agenda of new value systems in food and agriculture?

A: Propositions to farmers in developing countries like access to finance, fertilizer, and roads is part of the needed support and often already provided. But it is not sufficient a proposition to create new entrepreneurial zest. Such propositions merely reinforce the current contracting positions of farmers, and we all agree that this is not a very attractive position.

There are also calls for structural reforms in agriculture, like disowning small and uneconomic holdings, thereby providing room for large scale investment. But we then get back into the old redistribution dilemma, and consequent problems.

I think that relations in agriculture will become more dependent and thus more specific, given the business environment we’re in now. It is high time we re-imagineer producers as suppliers, to producers as customers. My suggestion would be to start designing partnerships as you would a design a business model for your actual customers. This would create the much needed relations for joint value creation, and the sharing of returns. It would catalyze the innovation we need to create a sustainable foundation for food and agriculture.

————————–

I would like to thank Joost Guijt in directing some interesting contacts to my post, and inviting their response. Joost is a member of the Value Chain Generation, and developing the Cotton Coversations startup.

Although this post has been a sort of conversation with myself, I hope to invite more discussion in the commentary string below. I look forward to receiving your thoughts and responding!