[Ed. 17-10-2014 We have an updated version of this partnership tool]

Alex Osterwalder’s business model canvas is proving to be an indispensable tool in the process of business model innovation. It trawls your sets of ideas for those innovations where you can improve on, or create novelty in bringing value to the customer. Also, there are exciting new developments to this tool, such as the value proposition canvas, which can be used as a plugin. The business model canvas is ideal for gearing your business for market disruption, toppling your competitors with a proposition that best fits to current customer needs.

Yet, there is one important aspect in the process of market disruption, that the business model canvas doesn’t take into account in detail, namely the value network, located at the back-end of the business model. As Clay Christensen, and Richard Rosenbloom (1995) wrote,

“The key consideration is whether the performance attributes implicit in the innovation will be valued within networks already served by the innovator, or whether other networks must be addressed or new ones created in order to realize value for the innovation.”

Forging the value network partnerships, which are required to make your business model work, is not an easy task. Potential partner businesses are already part of other existing value networks, and it is often not self-evident for them to engage with you in a partnership; they would rather stay in the relations they’re currently in. The upshot is that in order to realize a new business model, we not only need to convince our end users to prefer our idea, but we also have to motivate others within the value network to stop using our competitors. In this blog post I will present a prototype of a new business tool, that helps you in designing your partnerships, and intends to work seamlessly together with the business model canvas.

Available tools

It is my experience in discussing key partnerships with the business model canvas, that the discussion remains constrained to what I would need as a complement to my own business model, ie. what I would like to use my value network for. But a partnership is not just about my business model. It is a two-way relation. The questions I see myself asking in addition are:

- What position do I have in approaching potential partners? What can I offer that is of value to them?

- How can I assess the balance between what I offer my partner, and what I obtain in return?

- How can I best utilize these returns from my partnership for use in my own business model?

… and I keep guessing about the answers.

There are tools out there, value mapping being the most prominent of them. You can find a great feature of this tool in Vijay Kumar’s latest: 101 Design Methods. However, the inherent problem with this tool is that is primarily an analytical tool. It does not carry the conversation forward to creating the actionable hypotheses, which are required to validate a new business model. Just like the business model canvas, value mapping only provides guidance on possible outcomes for thinking about partnerships, not on how to specifically arrive at an outcome. There is thus a need for asking even better questions about your business model, making your thinking on partnerships more granular.

A prototype tool for discussing partnerships

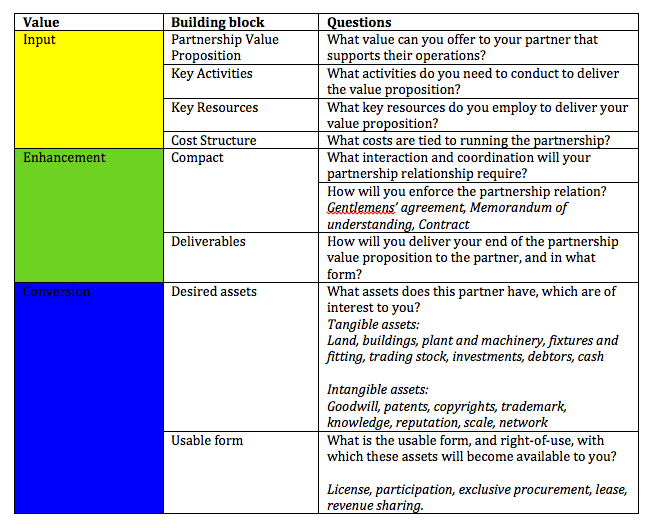

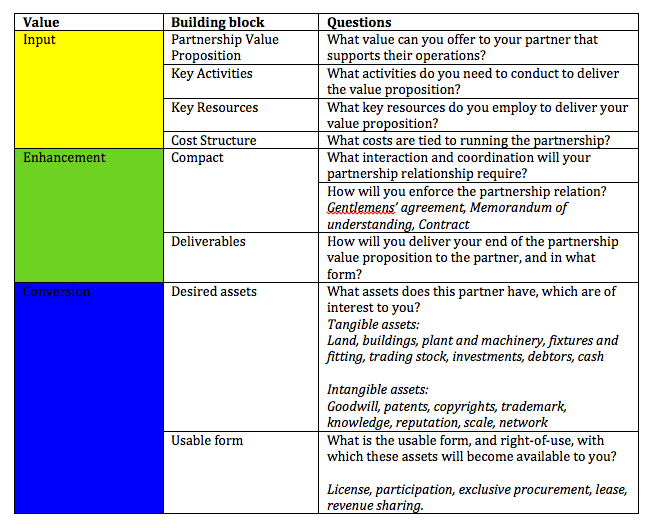

Something that comes closer to a resolve of this issue is the value network exchange process between two partners that Verna Allee (2008) describes in het work. Verna defines an exchange relation in a value network as a 3 step process:

- value input to the relationship (what do you bring to the table?)

- value enhancement (how can you enhance the value you can provide to your partner?)

- value conversion (how can you make use of the value that your partner holds?)

Expanding on this, I’ve broken these 3 steps down into 8 building blocks. Each building block contains its own questions that need to be asked in order to achieve the flow of value between your business model and a specific partner.

The content of this table can be rendered into a canvas structure. I have dubbed this the partnership proposition canvas.

The content of this table can be rendered into a canvas structure. I have dubbed this the partnership proposition canvas.

The partnership proposition canvas (v0.4): rendered from The Business Model Canvas (BusinessModelGeneration.com)

and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Un-ported License

How does the partnership proposition canvas work?

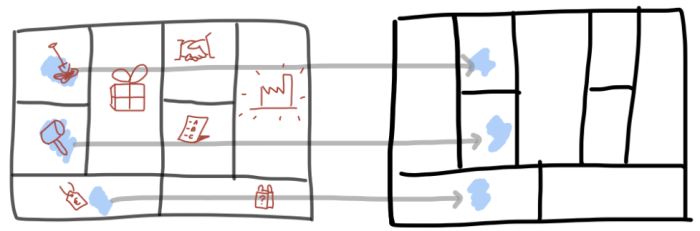

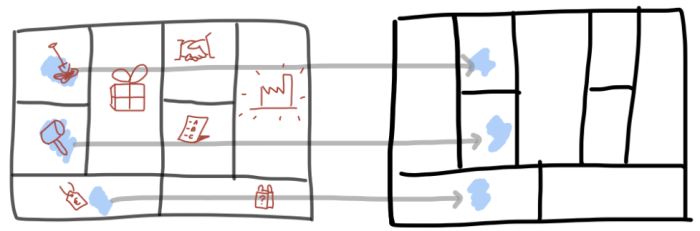

This canvas can be used either as a stand-alone tool, or in conjoint design with the business model canvas, as a zoom-in tool. You can use the partnership proposition canvas when you have validated the primary hypotheses relating to your value proposition-customer fit, and are looking to validate the rest of your business model. As Steve Blank explains in the (free!) Udacity Lean Launch Pad class: you can’t begin early enough with exploring potential partnerships.

The partnership proposition canvas has a two level relation with the business model canvas. First, key activities and key resources need to match in both. Secondly, “usable forms” in the partnership proposition canvas need to be relevant and applicable in any of the other building blocks of the business model canvas. This way you can indicate how a specific partnership adds value. The added value from your partnership can be evaluated by comparing the cost structure of the partnership, with the returns from application of the “usable forms” in your business model canvas.

Matching the partnership proposition canvas with the back-end of the business model canvas

The “usable form” building block should contain elements, which fit back into the business model canvas.

2 Examples

I’ve worked out two cases to demonstrate how the partnership proposition canvas works. The first is case of a company that has really taken its partnership strategy to the next level: the relation between Nespresso and its machine manufacturers. The second is a relationship gone sour: the relation between Apple, and its component manufacturer Samsung.

Nespresso and the machine manufacturers

Nespresso’s business model is famous for the relation it has set up with its partners, the machine manufacturers. The manufacturers have their own distribution channels through which they market their versions of the Nespresso machines. This dramatically increases the reach of the Nespresso concept, because once you buy the machine, you’re also stuck to buying the coffee pods.

But what would compel these manufacturers to make their distribution channels available? The partnership proposition canvas below shows how this is done

Machine manufactures have 3 assets that Nespresso doesn’t have, namely manufacturing facilities, a product distribution network, and product marketing. These are the desired assets that Nespresso wants to make use of.

Nespresso offers manufacturers three propositions: a license for using their technology to build the machines, a co-branding opportunity for marketing them, and providing a one-stop-shop for product returns. Nespresso’s condition for giving out this proposition is that the manufacturer co-designs its machines with Nespresso, and that they co-design the machine advertisements. This is firstly to safeguard the overall look and feel of the Nespresso concept. Also this compact supports changes to machine designs as the Nespresso R&D department periodically comes up with new technologies. As a deliverable to the arrangement, Nespresso includes the machines in their advertisement activities. On top of that Nespresso also offers to market the machines through its own Nespress.com and flagship stores, and defective machines back if they’re still under warranty.

What does Nespresso get in return that it can utilize for its own business model? Firstly of course, the mentioned access to the manufacturer’s distribution channel. But there’s more! The offer is apparently so appealing to manufacturers, that Nespresso is even able to seize a percentage of the sales of the machine through the Nespresso stores out of the deal, as well as a small license fee. When looking at the bottom line of this partnership, it creates more than enough value to offset the cost of running the partnership.

Apple and Samsung

The Apple-Samsung relationship dates back to 2005. Apple was looking for a stable supplier that could realize the replacement of the hard disk drive in its iPods with flash memory, and could at the same time meet the supply requirement for its upcoming line of other portable devices. At that time there weren’t many players out there who could supply that technology at the volumes and quality required by Apple: “Whoever controls flash is going to control this space in consumer electronics,” Steve Jobs said. Not only did Samsung fit the requirement as a supplier of flash memory, it also would deliver processors, and screens of high quality for iPods, iPhones, and iPads, fitting to Apple’s huge quality and energy saving demands.

So, what does this partnership look like?

Apple offers Samsung an exclusive procurement relation, where Apple will only buy its desired components from Samsung on a long-term basis. The steady growth in sales of i-devices backs the long term value of the proposal. Also, joint development of processors is a crucial part of the deal, as that requires capabilities that Apple doesn’t have on itself. As a deliverable, Apple purchases components, and shares sales projections, so that Samsung can coordinate its supply. The tricky bit of this arrangement is though that Samsung has also become very active on the mobile devices market since initiation of this partnership on 2005. That’s why the compact includes a confidentiality agreement, where Samsung’s components division is forbidden to share Apple sales forecasts with its mobile devices division.

Currently this relationship appears to be outlasted. Where Apple initially took advantage of the fact that Samsung was the largest manufacturer of flash drives in the early days when sales for the iPod really started to grow, Samsung has now turned into Apple’s main competitor on the mobile devices market. The confidentiality arrangement is put under pressure as the rivalry between the two companies on the consumer market heightens. Now that Samsung’s advantage as a flash drive manufacturer has lost significance due to more able rivals being active on the market, and due to the fact that it is directly competing with Apple, the relationship is downgraded. It is reduced to a basic component supplier relationship with limited added value (and potentially it is even a leaky risk!). Quite clearly, the relation is under pressure, and Apple needs to innovate with new relations and new partners.

Wrap-up

The partnership proposition canvas is a first attempt at creating an actionable tool that can support design from the back-end of the business model. It is informed by value web mapping tools that analyze how an industry’s value network exchanges value. Insights from such analytical tools can be used in the partnership proposition canvas to create actionable hypotheses for experimenting with new relationships in your value network, helping you build a strong business model.

The tool is still at an early stage and will be prototyped by more practitioners over the coming weeks. I hope that this blog post has captured your interest. If so I would really like to invite you to give this canvas a spin, and provide me with straight up feedback on how it works for you. More to come in this space!

Download the partnership proposition canvas template in powerpoint with stickies here:

Key take aways:

1) Value networks matter for business model design

2) Your key partner relations are more specific than mere supplier relations. You are often looking for complex forms of (non-monetary) value from your partners to support your own business model operations, and you need to deliver something matching in return.

3) Your partnership is temporary. What you need in search mode is different than the partnership you will need in execution mode, and even then your relations won’t last forever. Your partnership is thus likely to develop over the period of developing your business. The partnership proposition canvas can help you adapt to those upcoming requirements.

—————–

I would like to express my gratitude to Ernst Houdkamp for reviewing this blog post before publishing, encouraging me to make it as simple as possible. I hope this has worked out. I will be prototyping this canvas together with Ernst over the coming weeks to observe how it is used and learn about the needed refinements.

Literature used:

Allee, V. (2008), “Value network analysis and value conversion of tangible and intangible assets” Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 9 Nr. 1, pp 5-24

Christensen, C.M. and Rosenbloom, R.S. (1995), “Explaining the attacker’s advantage: technological paradigms, organizational dynamics, and the value network” Research Policy, 24, pp. 233-257