Value chain analysis is one of the most used approaches to designing private sector development projects. It helps to obtain an overview of all the relevant details relating to how a value chain functions. Value chain analysis looks at relations, supporting policy and business environment. It utilizes that analysis as a step-up to designing development opportunities.

Generic value chain

Value chain analysis has its roots in Porter’s sector analysis approach. It takes the perspective of competitive advantage in looking for business solutions (ie. position in relation to suppliers, bargaining power of customers, influence of new entrants, and threat of substitute products). However, current global market dynamics are very much in disfavor of sector approaches. Industry boundaries are obscuring as seemingly divergent market platforms are able to integrate and make innovative and powerful market combinations (mobile, payments, electricity, entertainment, etc).

Under these current conditions, the Porter approach has lost its ability to project towards the future. Providing the highest customer value is what will lead to a company’s advantage in the coming times, rather than the ability to contain market value within industry boundaries. (Read an excellent account on the demise of Porter’s 5-forces model, through the lens of the recent bankruptcy of the Monitor consulting group by Steve Denning). The longevity of insights captured with value chain analysis is thus eroding. Insights won’t last for as long as they should last to run value chain development projects for the 4-5 year duration that they usually do.

Development in our development tools

Despite this disability, value chain analysis as it is, is the dominant method that the development sector has to formulate development program goals and objectives. The leading, and most rigorous documentation of value chain development approaches is provided by the ILO with their Value Chain Development Guide (I performed as a tutor for a semester some years back for their online course for development practitioners). This method, in essence, attempts to create market innovation opportunities and guide their development in such way that they will achieve a more sustainable outcome (relating predominantly to labor in the case of the ILO).

Programs are designed, based on sector and market information, focus group discussions with potential beneficiaries, and surveys. This information functions as the working assumption about targeted users’ needs for the duration of the project. But the method doesn’t advise on tight feedback loops that facilitate adaptive learning to incorporate new insights about the program’s targeted users, should the initial assumptions not check out. The method thus boils down to a prescriptive, non-iterative process of project execution, which abstracts from the end-user who is foreseen to adopt an innovation.

In recognition of the low rate of adoption of the ideas, which are brought to the world through conventional value chain approaches, the Gates Foundation sponsored the development of the Human Centered Design toolkit, executed by the prime of design firms, IDEO. The HCD approach looks at innovative and nimble user-centered design approaches for value chain development. The principles for the HCD toolkit were deduced from observing the working method applied by the development organization IDE in their field of advancing appropriate technology for water management in agriculture and rural sanitation.

The strength of the HCD toolkit is that it supports immersion activities, and helps development practitioners (being non-designers) to come to insights for defining the opportunity space with their targeted users for their business development projects. It fills in the gap that is left by the ILO’s value chain development approach. However, what the toolkit doesn’t provide is support to the process of prototyping, and validating the business models that would bring commercial viability to innovations. The HCD toolkit focuses on tailoring technology, and making it utile or desirable to target groups. What it lacks is a rigorous deconstruction of an innovation process (if any), which works towards a business model outcome that is feasible and desirable for the customer, and commercially viable. The HCD, as such, is somewhat of an island in value chain development approaches.

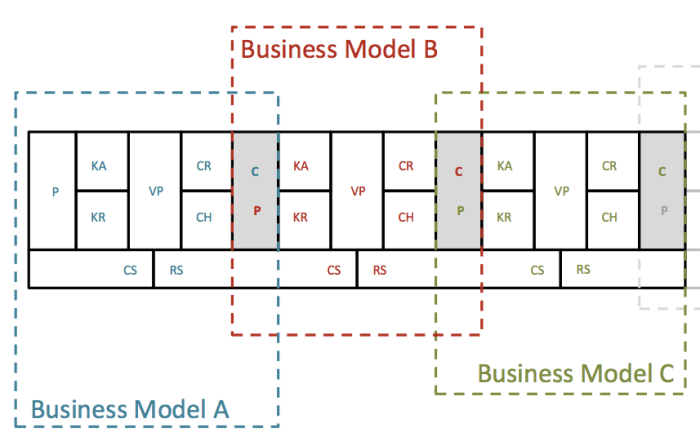

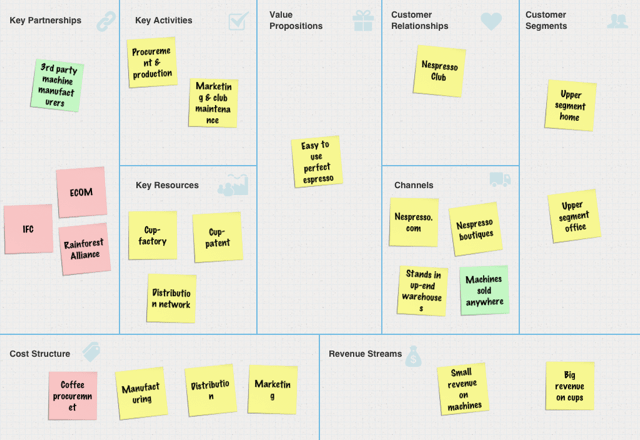

The last, and most recent example in the evolution of value chain development tools is the LINK methodology, developed by CIAT, again with support from the Gates Foundation. It is a first attempt at business model innovation in value chain development context. It fills in the gap of the business model perspective that is left by the HCD toolkit. LINK puts Alex Osterwalder’s business model canvas at the centerpiece of its process. The method extrapolates one of the functions of the business model canvas, namely sketching out how a business works. It then hard-links that function to describing how a value chain operates, by mapping out various business models in the sequential order of the value chain (see figure below). This description brings mutual understanding to all value chain community members, and is consequently used to design a new blueprint for a better, more inclusive, value chain.

Hard-linked business model canvases, describing a value chain

Though the business model canvas is prominently featured, the conceptual focus of the innovation that LINK proposes to work with is not the business model of a particular actor in the value chain. Rather LINK attempts to prescribe a collective value chain-level business model innovation to be executed by every (or a selection of) member(s) of the value chain. It is thus unclear what the method actually encourages to prototype. The process thereby abstracts from focus on the innovation opportunity space, and the required search for the business model that can best leverage that opportunity. LINK thus loses user focus and tends towards the same prescriptive limitations of the ILO value chain development approach.

So what now?

Although I have accentuated my reservations in review of these three value chain innovation methods, I must underline an interesting progress towards more design-minded approaches to value chain development. It’s encouraging to see that the academics, who have shaped the methods that development practitioners work with, are gradually moving towards approaches that are informed by design. As Don Norman wrote in a blog post some years ago, there is great value in combining the benefits of design and science thinking. Value chain design could well be such a field to make that combination.

But, the methods above also show that we are yet to come to a complete design process for value chain innovation. In parts, most tools are available. We now need to piece them together, in recognition that the underlying process provides for exploration, before arriving at a point where we can focus on refinement. Business model innovation is a method that can help achieve that. It is a method intended for discovery of what works and what doesn’t. It allows for flexible program adaptation to progressive learning, rather than prescription. By orienting on the customer, and designing a business model that is able to provide value for the customer, projects would retain focus on their innovation opportunity space.

Lastly, we need to accept in our value chain development ambitions, that the most influential business model in a value chain is the model that leverages an innovation opportunity space, and consequently molds a value chain: it doesn’t work the other way around. Desired changes in the value chain will follow from that dominant business model. The only influence development practitioners have is to provide principle design constraints regarding ethics, or sustainability that the innovation attempts to realize.

Takeaways

- A lot of the design tools for value chain development only partially appraise the design process. Taken as a whole they piece together as innovation process guidelines, which contains significant gaps.

- We should recognize that a development project is a faith-based initiative; outcomes and the necessary steps to arrive there are not known when you begin, they need to be discovered through exploration

- Discovery-based learning can be done by integrating more design methodology, taking a relentless user focus to discover actionable insights, defining minimum viable prototyping cycles, testing, learning, and adapting on the go

- We don’t need more manuals. We need to develop an innovation process with easy-to-use, easy to tailor tools, supported by a robust innovation process logic that helps projects progressively develop their decision making, rather than prescribes solutions.

——————

This is the third piece in a continuing series of posts (starting here) on what the role of human-centered design could be in development work. I’m working on this together with Niti Bhan, who will also be posting her observations at her Perspective blog. Posts are categorized as VCD