Nespresso is a machine-and-pod coffee concept for making espresso, developed by the food multinational Nestlé. By fitting an aluminium coffee pod into the machine, perfect espresso can be made at the push of a button. The Nespresso case is a famous example of business model innovation, propagated often by business model protagonists, and with good reason. It is one of the liveliest arguments that the future of competition will not so much be driven by innovation in products or services themselves, but by the activities surrounding the products and services that bring them to market. Specifically, what makes the Nespresso case appealing is that the model:

- lures clients through an upper segment marketing strategy, with George Clooney at the helm creating that “club” feeling

- ties customers directly to Nespresso through direct sales systems for the cups that go into the machine, both online (10 million online subscribers) and through boutiques (over 200 worldwide). This keeps margins close and warm for the company

- outsources production of the coffee machines to 3rd party manufacturers under “at cost” technology licensing. At the same time these manufacturers function as part of the distribution channel, as customers buying the machines are also tied to using the cups

- safeguards the major revenue stream through the cups with patents, and through Nespresso’s own high-tech processing facilities, which put coffee in the cups and seal them

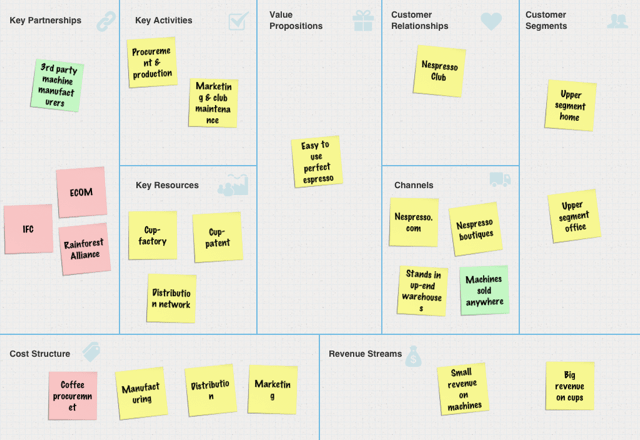

When the Nespresso business model is drawn out on the business model canvas, the overview looks more or less like this:

Nespresso’s business model wasn’t built in a day. Since its first patent in 1976, Nespresso fiddled around with the technology for 10 years, before incorporating the company in 1986. The company decided to service the business-to-business market in the 1990’s, in joint venture with a machine manufacturer that also maintained a sales force. This model failed, and almost bankrupted the company. Around 2000 Nespresso innovated in its business model and worked it out to what it currently is: a model which shows a year-on-year growth rate of around 25% (the fastest growing division at Nestlé), and which noted revenues of over Euro 2.4 billion in 2010.

Upstream business innovation

The case is most noted for its downstream business model innovation. In last few years however, interesting things have started to happen upstream as well in the company’s sourcing practices. The company’s bullish growth rates have put pressure on sourcing specialty coffees. Nestlé claims that only 1-2% of coffee produced in the world fits to their quality requirements for Nespresso, and competition for sourcing in this segment is fierce. In order to provide the distinctive coffee quality and aromatic characteristics, farms need to fit to a rare combination of several specific production parameters of soil type, altitude, and vegetation. Scarcity is thus starting to work on the business model, and this has pushed Nespresso to refine its sourcing practice, where closer relations with farmers are key.

The sourcing model is called the Nespresso AAA Sustainable Quality™ Program. Nespresso targets the farmers, or rather clusters of farmers (farmer clubs), that fit to the quality specifications it needs in Brazil, Colombia, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and India. The program focuses on quality, environmental and social sustainability, and productivity (further details of the program can be found here).

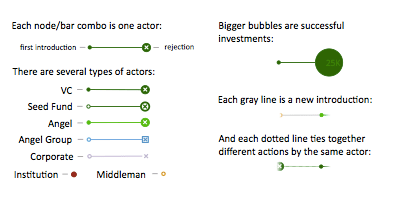

The program is operationalized by a consortium of several distinct partners. The partnership constitutes a business model in itself. This business model (depicted below) involves the following key partners:

- the commodity trader ECOM (marked purple). Farmers are reached through three channels: extension, credit, and trade, all organized by the commodity trader ECOM. Relations with farmers are built through the farmer club, which maintains a progressive quality segmentation of Cherry, Parchment, and Gold. The quality level is determined through an assessment of production practices by ECOM’s local extension support staff. The quality of coffee from each cluster is verified by Nespresso in Avenches (Switzerland), allowing for full product traceability from origin to pod.

- the environmental NGO Rainforest Alliance (RFA- marked in green). Sustainability performance of farmers involved is measured according to a watered down version of the RFA sustainbility standard, tailored to the Nespresso premium quality demands. In order to assess performance RFA has developed a tool called TASQ™, which can be used by producers for self-assessment and for verification by RFA as outside party at the same time.

- the financier International Finance Corporation (IFC- marked in orange). The IFC provides the program with USD 750k of the 1.5 million required for technical assistance (eg. developing the TASQ™ tool, and the extension system for farmers). Also IFC provides ECOM with USD 25 million of debt finance to support farmers in buying inputs for production and financing trade.

- Nespresso (marked in yellow) provides a modest role in the model by selecting farmers and providing product quality feedback on the coffee it purchases from the farmers involved in the program.

Drawn out on another business model canvas, the sourcing model looks like this:

Upstream Impact

According to Nespresso’s own statements, the program is working out very well. It claims to be able to reach its target of buying 1.3 million bags of coffee (60 kg. per bag) under the AAA program in 2013, corresponding to 80% of Nespresso’s requirement. Also Nespresso states that farmers are paid a price which is 30-40% above prices which are paid for regular quality coffee at the New York Stock Exchange, and 10-15% above prices paid for top quality. Furthermore the company claims to pay over 75% of the export value directly to farmers. As a result 40.000 producers supplied 60% of Nespresso’s coffee in 2010, and in 2013 this number is expected to reach 80.000. An impact assessment report by the IFC has shown that farmers’ club incomes are 27% higher than those from clusters of farmers which are outside of the program in Mexico and Guatemala. A small work-around of the figures shows that procurement of coffee is around 10-20% of the business model’s cost structure. This is very low by food industry standards and a very small price to pay for so much alleged positive impact.

In perspective

These types of partnership models are increasingly appearing in food and agriculture value chains of late. They are generally a response to pressures on resources and global commodity prices, where downstream companies build closer relations with suppliers in order to secure their production base. Regarding the Nespresso partnership the following observations can be made in SWOT form:

| Strengths: The model provides a low risk venture into the value chain for securing supply. Most of the funding and activities are conducted by Nespresso’s partners | Weaknesses: The sustainability performance is not likely to be high. The model is deliberately progressive, but the standards chosen for AAA quality are a selection amongst the Rainforest Alliance certification standards |

| Opportunities: The partnership is very flexible. It is already being expanded with other traders which can fullfill the role of ECOM (as shown by Cranfield’s study into the partnership here and here). As long as the trading company is substantial in size, and has local presence with farmers, it can be fit in with the program. For the sourcing model this means that Nespresso can start up new specialty coffee product ranges with new partners, sourced from remote areas in the world with distinct characteristics | Threats: It is as yet unclear what percentage of total production of the AAA farmers is actually bought by Nespresso, but it is likely not to be everything. Farmers are required to sell their remaining produce to other buyers, who are likely to have lower quality demands and therefore prices. If volumes bought by Nespresso are too small, then farmers could loose the incentive to produce against Nespresso’s high quality standards. |

As a whole, the Nespresso case is a very compelling case of business model innovation for both downstream and upstream segments, and holds potential for improving sustainability of the whole value chain. The most important observations for value chain innovation are that:

- the branding firm’s business model design matters for sustainable development in value chains. The Nespresso case has shown that value chain development entails designing compatible business models at the level of the lead firm, and at the level of suppliers. Nespresso’s continuing changes in its models both down and upstream have meant that is has been able to refine a fitting match. This design process is paying off well for the company and it is known to pay off for other companies using such principles as well.

- business models are in constant development. Some leading brand firms are ready to engage in business model innovation in their upstream segments, some are not. Nespresso has taken roughly 25 years before it started engaging with its producers. Business model innovation should only be started with firms that are ready to commit themselves to experimentation, learning, and change.

- despite taking leadership in value chain development, Nespresso is not active itself in execution of its sourcing model. There are an estimated 7 people working on the sourcing program from Nespresso’s side, in a company with currently over 5.000 employees, of which 70% belong to the sales force. This is a very small extra cost to operations of the company

- certification is not the driver for sustainability, but the lead firm business model is. The premium price was installed as an incentive for producers to deliver AAA quality coffee, and this could only be offered by Nespresso’s business model which has created a leadership position for the company in a premium quality market. The question remains what the overall impact will be on environmental sustainability, but the company has taken its value chain a step in the right direction.

If you want to learn more about how to design partnerships like Nespresso, check out our trainings options!

———————–

The business models were drawn using the Business Model Toolbox iPad app, available on the AppStore.