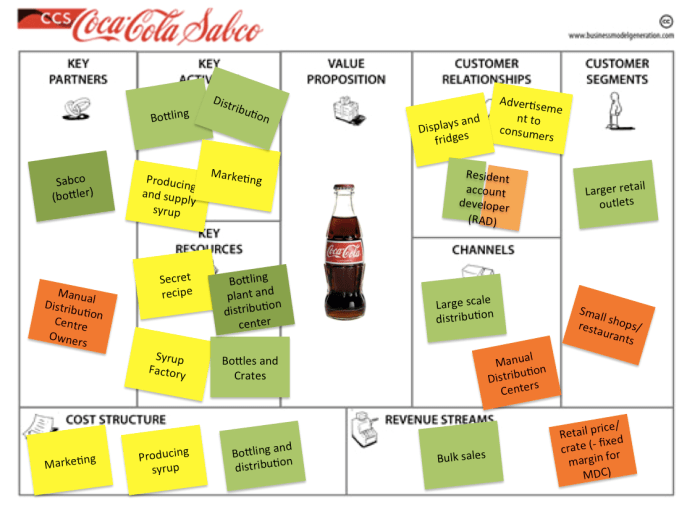

For the business model work I do abroad, for instance in Africa, I often need to adapt the case material a bit to the local context, when introducing the business model canvas. A really interesting case for doing that is the Coca-Cola case for Eastern Africa (everybody enjoys Coke, right?). Have a look at the worked out canvas, and I’ll explain the intriguing aspects about this case below.

The first thing people come to realize when working on the case, is that it is not Coca-Cola itself that runs the show. In fact it is a joint venture between the Coca-Cola Company and the bottler & distributor Sabco. Together they serve the larger part of Eastern Africa as Coca-Cola Sabco (CCS). Coke supplies its secret ingredient from its secret ingredient syrup factory, which is then mixed and distributed by their partner. Also Coke is involved heavily in marketing the brand (of course!). The involvement of the Coca-Cola company in the model (yellow stickies) as a whole is actually fairly limited, most of the work is done by their partner (green stickies)! Tell-tale sign of a well thought through business model.

Things get really interesting when you look at the customer segments. There are two basic segments, larger retail outlets, and small shops and restaurants. Now, the latter actually represents the largest market, but there is an inherent distribution problem there. How do you reach this large, and fragmented market in congested urban areas?

As a solution, CCS started experimenting with a system of Manual Distribution Centers (MDC’s, marked with orange stickies). These centers are owned by independent entrepreneurs who coordinate distribution to the small shops and restaurants. MDC owners invest up front in things like crates, bottles, push carts, and they hire the labor for distribution. CCS sales agents out in the field (called resident account developers) maintain relations with the customers, and try to get their orders out with sales price arrangements. The MDC’s then deliver the order, and receive the payment.

Under this system, prices are very much under control of CCS. They determine at what price they sell to the MDC’s. Also they determine what price levels are arranged at the end with the customers. What remains in between is for the MDC.

My take-away on the case

This MDC-system is heralded as a great success of inclusive innovation by the donor agencies who helped CCS set up the MDC systems. In 2010 it was reported that MDC’s represent often over 80% of distributed sales volume in East African countries, with over 2,200 MDC’s in operation. The model gives CCS full access to a fine-grained distribution network, and control over distribution, placement, and pricing, without having to do the physical work and coordination. A fine example of business model adaption for serving emerging markets, and a really strong case in the use of partnerships in the model.

Although I really like the case for its business model, I’m still left with some missing insights on the relation between the MDC’s and the people who actually ship the product to the customer. The case has been documented by many organizations but I have yet to find out about the system by which laborers are remunerated for their work. With CCS having so much control over the pricing, I wonder what efficiencies are employed to maintain margins for the MDC’s…. any thoughts? I have a snippet of evidence on the arm’s-length coordination that takes place with the hawkers here.