A scalable business idea has to run through and pass a continuous testing trial, before it actually becomes scalable. Once an idea gains traction in the market, there is an argument for it’s growth potential. What consequently enables ideas to scale in practice is generally finding an investor who can amplify the idea. Investors that don’t buy the traction idea of achieving scale will refuse to fund. On the other hand, those that will contribute funding are the same people which will help it scale; funders are part of the scaling solution. A very powerful business development mechanism.

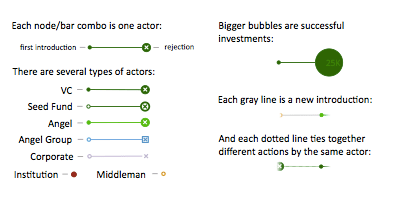

Finding your (right) funder is a very complex process in business. Brendan Baker‘s (AngelList.com) analysis on seed funding (below), shows that finding a funder is “messy” non-lineair process involving a wide array of actors: brokers, various types of investors, and even network cataracts where a potential investor will refuse to invest, but proves to be able to provide useful referrals for further attempts. If the idea survives this trajectory and adapts if necessary, if it can convince the various investors that it is indeed a valid investment to make, then there is a good chance the idea will scale. If it doesn’t then the idea will never really see the light of day. A clear enough selection mechanism for achieving scale.

There’s a lot of talk on achieving the need for scale in business in development interventions too. The basic concept here is to support a business or preferably a market system into economic viability with public funding, and then retract at “the right moment” to let autonomous market forces take over. This concept is driven by the enticing experiment of mimicking the powerful market dynamic of scaling.

But, there is a lack of introspect into using the ways that markets achieve scale in the business in development approaches. Case in point is simply the lack of scaling results of implemented ideas. Scaling is not happening!

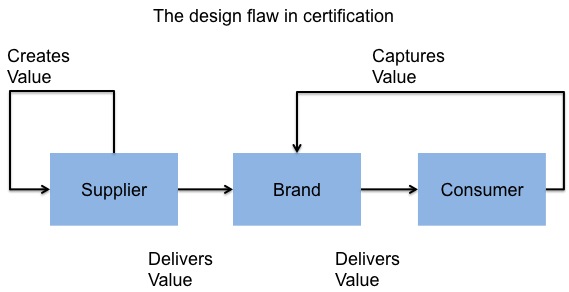

An important source of the problem is that the design of business in development ideas is too much under control of the development worker, or a group of development policy deciders. Ideas are linearly defined: the donor thinks of a concept and then implements it according to those policy lines. The selection process of project ideas is completed before implementation, and the idea is instantaneously granted life based on paper. Donors’ own in-house developed policy criteria for granting funds to an idea thus count more than actual market traction for the idea. It is thus the donor that wishes to convince the grantee, rather than the grantee wishing to convince the donor.

Most business in development ideas thus don’t go through the body of constructive market critique, that commercial ideas have to undergo, as in the line-‘n-bubble figure above. The upshot is that the difference between good ideas and bad ones is only determined at the end of the project cycle (if they are subjected to a proper impact evaluation that is), when all resources have been spent. This is a very long feed back loop for selecting ideas, which takes meek ideas too far for too long, and it frustrates learning processes.

Now, in order to make more effective use of the market-based scaling mechanism, there are two general points to trial in generating scalable business in development ideas. Firstly, donors should find a way to integrate the social interaction found in allocation of commercial capital in their idea formation process to let the strongest ideas emerge (whether it’s their own, or the idea has come to them). Don’t go for the full-appropriation approach to funding ideas. Rather, refer to other members of the donor community or commercial parties to review and fund parts of the idea you are less experienced with or less focussed on. Use the community to shape the strongest ideas.

Secondly, donors need to recognize that the diversity in types of business operating in a sector matters. Steve Blank recently provided a seminal post on this. Some types of business are just not meant to scale, whilst other types are built for it. Select the ones that do!

So the points to take home are to scrutinize the ideas you fund, and understand the nature of the beast you are going to feed. That’s the only way of obtaining as much assurance as feasibly possible that utilizing capital contribution will fire the mechanisms that expand business.